- Home

- Bengie Molina

Molina Page 11

Molina Read online

Page 11

I got plenty of practice. I caught about three hundred pitches while warming up five or six pitchers before games. I warmed up two or three relievers during the game. Sometimes I’d catch guys who weren’t even on the team. They were aspiring pitchers who were friends of the Mayaguez players. I tried to compensate for my lack of real playing time by creating scenarios in my head the way Pai did at practices.

“Runner on third, batter bunts!” I’d tell myself. I’d catch the pitch then leap to my feet as if scrambling for the bunt and swipe at an imaginary runner trying to score. I lunged at every off-target pitch as if the deciding run of the World Series was at stake. I blocked balls with my arms and legs, my chest and shoulders, experimenting to see what worked.

“What are you doing?” a pitcher barked at me one day in the bullpen.

I didn’t know what he was talking about.

“Why are you doing that?”

I stood. “What?”

“Your butt up in the air.”

“My butt?”

“Let me tell you, the really good catchers sit down and relax when there’s no one on. You’re always catching like there’s somebody on. Makes me nervous. Makes me think I have to throw a strike. Sit down. Low.”

I caught from the higher crouch because I could more easily leap up to throw a runner out or field a bunt. But I lowered my rear so it was almost resting on my heels. I spread out my knees.

“There you go,” the pitcher said.

I put down two fingers for a curveball.

He nodded and went into his windup.

I rose into the higher crouch.

“No! No! Sit down! Just make me throw the pitch.”

“This is the only way I know.”

I felt more able to block pitches from the higher crouch.

He dropped his glove, came back to the plate, and actually showed me how to squat low and give him a big, steady target.

It felt weird, but I understood that catchers do whatever makes their pitchers comfortable. I eventually became more relaxed in the lower crouch, and over the long haul, it put less pressure on my legs.

But during those early seasons, while I was still learning, I ached from head to toe. I’d arrive home from Mayaguez around one thirty in the morning, fill a couple of socks with ice, and lay them on my battered arms and legs.

I savored the off days, not just for the rest but for the time I could spend with my family. I missed them when I was in the States. I still felt like my real life was going on without me. My favorite place in the world was Mai and Pai’s house, with Mai and Pai’s bickering and the smell of Mai’s cooking.

“Arroz con gandules again?!” Pai would moan when he lifted the lid off a pot on the stove. “Good for Pinky. He’s going to love eating this.” Pinky was the dog.

Mai would hustle him out of the kitchen. “Oh, go sit down!”

I especially loved the evenings when the house filled with neighbors and friends and Pai got tipsy enough to be silly. Mai would put a pot of soup on the stove. Pai fired up the hibachi in the carport. Everyone pulled up lawn chairs and drank beer or poured a shot of Finlandia into plastic cups of Pai’s grapefruit juice. They played dominoes. Babies were passed from lap to lap. Toddlers waddled around. After Mai bought Pai a karaoke machine for his birthday, there was lots of singing. Once Pai had enough Coors Light or vodka in him, he’d belt out songs by Marc Anthony and José José and Tito Nieves. He’d make hilarious attempts to dance to reggaeton and bachata, pulling the neighbor ladies up from their chairs to dance with him.

On Mai and Pai’s anniversary that winter, the house was packed as usual. The concrete floor of the carport, where everyone danced, was slick from rain. Our neighbor Lourdes slipped and fell on her backside. Pai tried to help her up, but when he fell too, he had such a laughing fit he kept falling with every attempt to lift Lourdes and himself, which threw them both into convulsions and got everyone else laughing.

Later in the evening, Vitin made a toast and called for Pai to give his bride a kiss, well aware of Pai’s discomfort with public affection. Pai made a face, and everyone hooted at him to kiss Mai. Mai puckered her lips. She was having a great time. Pai laughed and finally kissed her full on the mouth to thunderous cheers. For the rest of the night, Mai was all over him, kissing him at every turn, making everyone laugh.

The next day, when Pai saw Lourdes at the field, he teased her. “You left such a hole in the floor that I have to go get cement to patch it up!”

Increasingly, though, I noticed Pai getting angry over little things I did. Late one night when I was sitting with ice on my arms and legs, Mai padded into the kitchen.

“You eat?” she asked.

I was tired and sore after long bullpen sessions and the two-and-a-half-hour drive in the cranky Nova.

“How would I eat? I have no money and nothing’s open this late anyway.”

Pai’s voice suddenly boomed from the bedroom.

“Why do you say that to your mom?”

“I just said I hadn’t eaten,” I called back.

“You’re making her feel bad because she didn’t cook for you. Don’t talk to her like that!”

Mai shook her head and waved her hand, indicating I should ignore Pai. I wasn’t sure why he was snapping at me. Maybe it was his way of letting me know he was still the man of the house. As if there could ever be any question on that front.

But those were small things. I still got up to drive Pai if I was using the Nova. I hated getting up; I needed the sleep. But I liked having Pai to myself. He talked to me about the special relationship catchers had to have with pitchers. A catcher was like a coach on the field. The one guy who always had to be a grown-up. He had to know his pitcher better than the pitcher knew himself. When a pitcher struggled, a catcher had to get him on track. Maybe slow down the pace. Or quicken it. Maybe call only breaking balls. Maybe kick him in the butt. Maybe tell him he’s a stud and the whole team is behind him. Whatever worked for that particular pitcher.

But I wasn’t playing in any games, so I couldn’t put Pai’s advice into practice. Sometimes I was just trying to survive. One night late in a game, the bullpen coach summoned me to warm up a relief pitcher named Roberto Hernandez. “This should be entertaining,” I heard one of the other pitchers say.

I knew about Hernandez. He was a beast. He was said to throw 100 mph and had a crazy split-finger fastball that moved all over the place. It would be tough enough to catch Hernandez during the day, but in the murky nighttime bullpen I was a dead man. Guys in the bullpen settled into their seats as if for a performance. They crossed their arms and smiled.

Hernandez went into his windup. He threw. The ball hit my mitt like a bullet. Thwap! Oh my God. That was what 100 mph looked like. I never moved my glove. If the ball had been a little higher or lower, it might have blown right through me like a cartoon missile.

I tossed the ball back. I couldn’t believe anybody could throw that hard. I had been a catcher for all of a year. I didn’t know how to catch this guy. I stretched my eyes as wide as I could. Focus. Watch the hand. Lock in.

Windup. Throw. Thwap!

Windup. Throw. Thwap!

One after another. Right into my mitt.

I didn’t miss a pitch.

When I finished, I could barely straighten from my crouch. My heart was pounding and my mouth was dry.

“Good job, kid,” the bullpen coach said.

I smiled all the way home. I’d have a good story to tell Pai in the morning.

KYSHLY WAS BORN on November 25 at the Bayamón hospital where Cheo and Yadier had been born. I couldn’t take my eyes off her. The way her tiny hands closed around my finger. Her chubby legs kicking. Her eyebrows bunching up like a worried old lady.

“Becoming a father changes everything,” Pai told me. “Now you have something to live for.”

My love for her was unlike anything I’d ever felt. It was thrilling and terrifying. I hovered over Yadier and Cheo when they cradled h

er.

“Her head! Hold her head!”

Kyshly slept in a secondhand crib in our room in Mai and Pai’s house. There was no baby shower, though my aunts and uncles gave what gifts they could: blankets, bottles, rattles. I earned six hundred dollars a month with Mayaguez, not enough to cover doctor bills and everything else the baby needed. We applied for welfare and began receiving food and milk every two weeks.

Two months after Kyshly was born, three of my Mayaguez teammates intercepted me when I arrived at the clubhouse. Doug Brocail, Robin Jennings, and Kerry Taylor were all Major Leaguers.

“We want to give you something,” Brocail said. He pointed to Jennings and Taylor. “He’s got two daughters. He’s got three. I got two.” They handed me three huge bags of baby clothes and toys. I couldn’t believe it. My wife cried when I arrived home with the gifts.

By the end of the Mayaguez season, I calculated I had caught about twenty-two thousand pitches. We made the playoffs. But I wasn’t eligible for the playoff bonus. As I was packing up my belongings in the clubhouse on the last day, a bunch of players appeared at my locker with a thick envelope.

“An appreciation from everybody,” one of the players said. “You worked your butt off.”

Inside was $1,500. A fortune. We’d have plenty for food and Pampers. We wouldn’t have to borrow money again from my father-in-law for plane tickets back to Arizona. I could buy a battery, spark plugs, and a windshield wiper motor for Pai’s Nova. The motor burned out again before I even left for Arizona.

THE BUZZ IN the Angels’ farm system the spring and summer of 1995 was about a twenty-four-year-old out of Georgia named Todd Greene. He had been drafted two years earlier. Now he was on his way to hitting forty home runs, the most by a minor leaguer in a decade. He had already been promoted to Triple A, the highest level in the minors.

And he was a catcher.

“Catcher of the Future,” the newspapers said.

I spent the 1995 season with the Angels’ High A team in Lake Elsinore, California, putting up solid numbers. Mayaguez invited me back for winter ball, this time as the backup catcher. I’d finally catch in actual games. But three days before the start of the season, Mayaguez signed San Diego Padres catcher Brian Johnson. He’d be the team’s starter. The domino effect knocked the previous starter to the backup spot—and me back to the bullpen.

For the second winter, I didn’t catch a single pitch in a real game. But I caught another twenty-two thousand pitches in the bullpen.

The following spring and summer, I was promoted to Double A. Todd Greene was again tearing up Triple A. By midseason, right on schedule, he got the call: He was going to The Show. He had earned it, no question. But what were my chances of cracking the Major Leagues with the Second Coming of Johnny Bench already behind the plate?

As soon as I mentioned Greene’s promotion on the phone to Pai, he shut me down. All you can control is you. Work hard. Keep learning. Talent carries you only so far. You carry yourself the rest of the way. I knew he was right. I had seen my old rookie-ball roommate, José, during the most recent spring training. He was no longer the sure thing with the rocket arm. He was out of shape, probably from too many beers and too much weed. He had lost the snap on his fastball. The Angels had demoted him to Single A. He had been such a natural. Baseball had looked so easy when he played it, the way I imagined Pai must have looked as a young man. I knew by then that even for naturals, nothing was guaranteed. So much can get in the way. Laziness. Injury. Attitude. Bad luck.

Which had it been for Pai?

IN THE WINTER of 1996, the Mayaguez dugout became my classroom, the best since Mrs. El-Khayyat’s. My teacher was a catcher named Sal Fasano.

I was on the actual roster for the first time. Sal was the No. 2 catcher and I was No. 3. He was only a few years older than I was and had made his Major League debut just a few months earlier with the Kansas City Royals. But he had been catching all his life.

“What would you call here?” Sal asked me. We were in the dugout in Mayaguez. The batter had chased three sliders away, fouling off one. Clearly he was struggling with the slider away.

“Another slider away,” I said.

“That’s not a good pitch here. The more he goes out there, the better he’s going to get at reaching it. Go fastball in. Straighten him up. Then go slider away again.”

It was how you set a trap for a batter.

That winter with Sal Fasano was like graduate school.

He showed me how to be quiet in my body behind the plate. Move nothing but the glove, and even that as little as possible. When the pitch is slightly out of the strike zone, shift the glove back into the strike zone and hold it still so the umpire can register its location.

“You’ll get more strike calls. Your pitchers will love you,” Sal said.

He told me never to face the umpire when you’re questioning a call. If you argue face-to-face, he’ll think you’re showing him up and he’ll make you pay.

Sal showed me how to position myself behind the plate to provide the biggest target for the pitcher. Never lean forward. It diminishes the target. Keep your back straight so your entire torso is visible.

He told me to look confident when I called a pitch so the pitcher felt confident, too. The catcher has to project calm and confidence to all his teammates. He’s the conductor. He initiates the action and sets the rhythm. He is the focal point of the field, where every run begins and ends. A good catcher sees all eight teammates, plus the batter and base runners, as a single entity, an ensemble, and he adjusts to the shifting circumstances.

Before games, Sal took me through reports on every opposing hitter. A guy with a slower swing wants sliders and curves. So you throw hard and in. A quick-bat guy likes fastballs in. Pitch him away. Notice who chases high and who chases low; who’ll take a pitch to the opposite field; who’s a hit-and-run threat; who’s a base stealer. Put yourself inside the batter’s head.

“But let’s say you know everything there is to know about a hitter,” Fasano said. “Let’s say you know he can’t hit a slider, so you want to call the slider. But say your pitcher’s slider isn’t working. What’s Plan B? You have to have a second option in your head at all times.”

I was the No. 3 catcher but played in a lot of games with different pitchers. I had caught all of them in the bullpen. But games were a different story. It wasn’t just about strategy and mechanics. Fasano taught me to watch the pitcher’s face and body language. Was he still thinking about the double he gave up? Was he annoyed with the second baseman’s throwing error? Was he losing his nerve? Did he need a pep talk? You had to know the styles and personalities of each pitcher, and you learned that only on the field. Did a pitcher respond to failure with productive anger? Did it make him even more competitive and determined? Or did it plunge him into a funk? A catcher had to manage the pitcher’s mood, coaxing and cajoling like a patient father. The catcher had to be the steadying influence, the soothing advisor who knows what the pitcher needs before the pitcher does.

The best catchers squat inside their pitchers’ brains.

As we watched together from the bench, Sal pointed out pitchers’ “tells”—small indications that a pitcher was fatigued or distracted or upset.

“See this guy? He’s creeping up in the zone. He’s tired. The catcher should be checking on him. See how much more he has.”

Fasano said he didn’t have a body part that hadn’t been hit by a pitch or foul tip. Toes, inside ankle, top of foot, inside part of heel, inside part of calf, inside part of knee, the knee itself, top of knee, quadriceps muscle, inside quad, biceps, belly, ribs, chest, neck, face, shoulder, arms. He said you could expect to get hit about five times a game. That doesn’t count the foul tips that glance off your glove and bend your thumb back. Sometimes, Sal said, you get hit so hard you’ll go to the mound to confer with your pitcher, or call for meaningless throws to hold a runner at first, just to buy a few seconds for the pain to subside. But if your pitcher�

��s on a roll, you don’t do anything. You ignore your own pain. You don’t want to disrupt his rhythm. A catcher is a warrior, strapping on his gear as if for battle. He keeps his back to the crowd. His eyes are on his teammates, watching out for them, protecting their turf.

Catching so many pitches in Mayaguez and in the minors had a side benefit: My hitting improved. I knew the grips and motions for different pitches, so I was beginning to recognize pitches before the pitcher even released the ball. A slider was more sideways in his hand. A fastball was all up-and-down motion. A curve came over the top. A change-up showed more of the ball.

I also had a better idea of what the pitcher was likely to throw. I’d think, If I was pitching against me, what would I call? I tried to think along with the pitcher. If he threw two curves in the dirt for balls, I could be pretty certain he wasn’t going to risk going down 3–0 by throwing another curve. I’d look for a fastball. I don’t know if I became a more athletic hitter, but catching had made me a smarter one.

THE ANGELS BUSTED me back to Single A to start the 1997 season. It was a numbers game, they said. Too many catchers, not enough spots. They wanted to promote Bret Hemphill from Single A to Double A. So that left me with Single A. I was furious. I’d had a good year in Double A. Done everything they had asked. And I get demoted?

All my underdog rage spewed through the phone lines to Puerto Rico.

“Pai, what else do I have to do? This is ridiculous.”

Pai didn’t answer.

“Pai?”

I wanted him to say something.

“Do you want come back to the factory?” he said.

“What?”

“Tío Papo can get you your old job back.”

Halfway through the season, Bret Hemphill went down with a shoulder injury. I returned to Double A. Todd Greene, meanwhile, had been demoted from his job as the backup catcher in the Major Leagues back to Triple A for more seasoning. He tore up Triple A pitchers like he always did, and soon he was back in the big leagues. Angels manager Terry Collins reiterated to reporters: “Todd Greene is the future.”

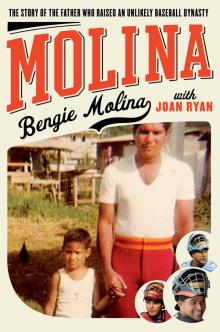

Molina

Molina