- Home

- Bengie Molina

Molina Page 16

Molina Read online

Page 16

I pushed myself so hard during rehab that the trainer ordered me to slow down. During games, I sat with Cheo in the dugout and talked about how he might handle this batter or that one, or what he could do to get the most out of the pitcher.

In June, Mai called in tears. Mami, her mother, had died. When Cheo and I were babies, Mami took care of him every morning while I was with Pai’s mother. In elementary school, my brothers, cousins, and I went to Mami’s house every day for lunch. She was in her eighties, but her death was a blow. Cheo and I flew to Puerto Rico for the funeral. I had never seen Mai so quiet. Her loss was so great that there were no words. Mami was buried in the old cemetery behind the junior high school in Vega Alta. Cheo, Yadier, my cousins, and I carried the casket.

When my hamstring healed and I returned to the lineup in late June, we were already eighteen games out of first place. Cheo returned to Salt Lake City. He returned two months later with the September call-ups. We became the first brothers to catch for the same Major League team since Amos and Lave Cross of the Louisville Colonels in 1887. Pretty amazing.

Mai and Pai flew to Tampa to watch us against the Devil Rays. It was their first time seeing either one of us in the Major Leagues. By then, Yadier was finished with his rookie league in Johnson City, Tennessee, so he joined Mai and Pai on the trip.

When I saw Pai in the stands, I couldn’t shake my nerves. What was he going to think? Why did I still feel I had something to prove to him? I went 0-for-3 with an RBI sacrifice fly. But we won, 2–1, and my pitchers gave up only four hits.

Afterward at dinner, I expected Pai to say something about my 0-for-3. I knew he was itching to help, to suggest a tweak, to remind me what I had learned on his field. Let the ball come to you. Keep your body straight, straight, straight. But he didn’t say a word. Maybe as a gesture of respect? Maybe he wanted me to ask?

The next day, Cheo started instead of me and struck out twice. As I drove the rental car to dinner, I whispered to Mai, “I’m going to get Pai fired up.”

“Hey, Cheo,” I said, “what happened today? You were swinging at balls in the dirt.”

Pai, in the backseat with Cheo, erupted.

“How many times do I tell you about swinging at balls in the dirt? You don’t learn!”

Cheo kicked my seat hard. “What are you doing?”

Mai and I laughed while Pai lectured Cheo for being too aggressive sometimes and not aggressive enough other times. “You have to have a plan up there!”

Okay, we were back to normal. Pai was always hard on Cheo and me. He was gentler with Yadier. The worst he’d say to Yadier after a bad at-bat was, “Yo bateo a ese pitcher hasta con los puños!” That pitcher’s so bad I could get a hit with my fists!

Maybe it was because Yadier was the baby. But I think he understood that criticism didn’t motivate Yadier. Cheo and I, on the other hand, seemed to have a perverse need to hear it, as if listening to Pai’s critique was a kind of absolution for our mistakes and we could let go of them and move on.

The Angels finished the 2001 season forty-one games out of first place, the worst showing in franchise history. Cheo had played in fifteen games, most of them when I was out with my hamstring injury. He was sent back down soon after Mai and Pai saw us in Florida. We didn’t get much time together as teammates.

In the off-season, my wife, the girls, and I moved into our new $240,000 house in Yuma: two stories, four bedrooms, big yard, pool. I slept in the guest room most nights. My wife and I were unhappy strangers who shared two beautiful daughters and little else.

WE WERE ALREADY ten games behind the first-place Mariners before the first month of the 2002 season had passed. The Mariners had swept us at our own ballpark. It was humiliating, like watching someone steal from your house. You want to go out and get your stuff back, and you want to inflict as much pain as possible on the thieves who took it. So when we flew into Seattle two weeks later, we were looking for payback. We wanted to show that their sweep was a fluke, that we were, in fact, the better team.

We lost the first game of the series 16–5.

Usually the clubhouse was a refuge, the place where you could be furious or idiotic and no one outside would ever know. You could let down your guard. You could rage, cry, dance, fight, belch, confront, console, and walk around naked. You could stay there as long as you needed after a game to turn yourself from an angry, frustrated, self-doubting baseball player into someone fit for normal society. The Code of the Clubhouse was the pro baseball version of the code drilled into me by Pai. Respect your team as you would your family. What happens among the players stays among the players. Don’t embarrass a teammate in public. Watch each other’s backs.

But every now and then the clubhouse was the opposite of a sanctuary. You wanted to get away from everything and everybody that reminded you of the humiliation you just endured.

We were slumped in front of our lockers, yanking off our uniforms as if they reeked from the stink of the game, when Scioscia charged in, swearing and kicking over trash cans and laundry bins. He picked up a chair and tossed it across the floor. He grabbed clothes from random lockers and flung them. No one moved a muscle. We had never seen him like this.

He upended a basket of dirty laundry. “This is what we are now!” he said, kicking the clothes. “Everything’s the pits! This team is the pits!”

Scioscia’s coaches were scattered behind him, arms folded across their chests, their eyes traveling from him to us, gauging the impact.

“Damn it! We’re embarrassing ourselves!” Scioscia raged.

I had seen managers in the minor leagues hurl bats across the floor and kick over chairs. Sometimes it seemed like a show, as if the guy had watched Bull Durham and figured that’s what he was supposed to do. But this was the real deal. Scioscia was pissed.

Then he stopped. He dragged his hand over his head. He took a deep breath. Every eye was on him.

“Okay, listen, this is where we are now,” he said, nodding toward the clumps of laundry. His voice was even. “We’re playing like garbage. We’re not playing together. We’re not picking each other up. We look like the team everybody out there thought we’d be. We’re better than that. You know we’re better than that. If we’re going to win, we’ve got to find a way to do it together. Nobody else is going to fix this for us. Nobody’s going to feel sorry for us.”

He scanned the room, looking at each guy as if sizing him up.

“I believe this team can win. Every coach in here believes this team can win. If we keep working hard and stick together, I promise you we’ll be fine.”

When the coaches left, All-Star outfielder Darin Erstad stood.

“We have to leave our egos at home. We have to play for the team. When you come to the park, you leave your egos outside.”

The next day we lost, 1–0.

Then we started winning. We beat Seattle in the third game of the series and won the next eight games in a row. We were finally playing our game: getting on base, working the count, hitting guys over, playing for each other. We were a little like Los Pobres, with a lot of long shots and underdogs. Five-foot-seven-inch shortstop David Eckstein got on base twenty-seven times by getting hit by pitches, leading the league in that category. We were generous in sharing info after our at-bats, telling the next guy what to look for. The camaraderie Scioscia had fostered over two seasons was finally translating into wins. In May, we were the hottest team in the Major Leagues.

I talked to Cheo every few days. He was in Triple A. Jorge Fabregas was still with the Angels as my backup. I was coming into my own as a catcher. I dug pitches out of the dirt and leaped into a throwing position in one motion. I lunged backhanded for wild pitches and used the momentum to pull me to my feet, ready to throw. Almost nothing got past me. I might have slowed down on the base paths but my reflexes behind the plate were quicker than they’d ever been. I wished Cheo had been there to see how much his lessons in spring training had helped me. I was throwing out 52 percent of ru

nners trying to steal, best in the league.

In late July, we were back in Seattle for a three-game series. Jamie had moved to Washington earlier in the season to help a friend get through a tough divorce. She was freelancing for Fox Sports Northwest. I missed seeing her in Anaheim, but we talked on the phone several times a week. Sometimes every day. It didn’t matter where we lived. I left tickets for her, her roommate, and her parents at Safeco Field then took them to dinner after the game. When I dropped Jamie and her roommate at their house, Jamie lingered by the door.

“I wish we saw each other more,” she said.

“Then let’s see each other more.”

“I mean I wish I still saw you at the park.”

“Come back to Anaheim.”

She laughed. “You should get back to the hotel and get some sleep.”

“Why do I feel you’re always pushing me away?”

Jamie let out a deep breath.

“I’m not. It’s just—” She stopped.

“What?” I asked.

“Listen, everything’s fine. Ignore me. Thanks for dinner.” She gave me a friendly hug. “Talk tomorrow?”

In August, the Angels traded Fabregas to the Brewers. Cheo was promoted to fill his spot. His name went back up on the locker one over from mine. He was a boost of energy for me in the dog days of August. We sat together on the plane and in the dugout. We shared cabs to the stadium. We talked baseball at the field. We talked baseball in the clubhouse. We talked baseball at P. F. Chang’s and Benihana. We talked baseball at the mall when we were killing time on the road. It was like being back in our bedroom in Espinosa, talking in low voices in the dark. After games, we separately called Mai and Pai from our hotel rooms.

“Now all I have to worry about is Yadier,” Pai said. Yadier was in Peoria, playing Single A ball for the Cardinals. Cheo and I talked to him as much as our schedules and his allowed.

“Hey, wait for me!” he’d say. “I’m going to get up there.”

We told him we had no doubt. He was better than both of us.

By season’s end, our pitching staff had allowed the fewest runs in the league. I got a fair amount of the credit, but much of that praise belonged to Cheo. He taught me and pushed me, and I did the same with him. He picked up on things I missed. Everything I did—calling pickoff plays, calling pitches, everything—was smarter and sharper because Cheo was with me.

We finished second in the AL West, good enough to get us into the American League Division Series for the first time in a generation. The bad news was we had to play the Yankees, American League champions four years running. Their roster was like a future Hall of Fame ballot: Derek Jeter, Roger Clemens, Andy Pettitte, Mariano Rivera, David Wells, Jason Giambi, Alfonso Soriano, Robin Ventura, Bernie Williams, Jorge Posada, Mike Mussina.

Pai couldn’t get off work, my daughters were in school in Yuma, and Jamie was in Seattle, so none of them (including Mai) came to New York. In one of the most stunning playoff upsets in years, we beat the Yankees, three games to one.

We faced the Minnesota Twins in the American League Championship Series. Mai and Pai still couldn’t come. But Cheo and I wrangled Yadier a pass so he could be on the field for batting practice. He traded in his Cardinals jersey for an Angels shirt and cap. “This is my team right now,” he said.

The Twins took the first game and we took the next two. In the fourth game, we were up 4–0 in the bottom of the seventh. I hit a screamer to center field. I rounded first and headed to second. I looked toward the third-base coach. He was waving me to third. Seriously? Me? Was he out of his mind?

So I kept chugging, running as fast as I could, praying to beat the throw. I slid into the bag. Safe! A completely improbable triple. In the dugout, my teammates were hooting and clapping and going crazy.

In his postgame press conference, Scioscia—no gazelle himself during his playing days—had some fun. “Triples and Bengie Molina are like going sixty miles an hour on the Hollywood Freeway. It doesn’t happen too often. Hey, my wife pregnant beats Bengie in a race.”

We won that game and the next to win the American League pennant. We poured out of the dugout, screaming and hugging one another. I ran straight for Cheo and we looked at each other for a moment in stunned disbelief.

“We’re going to the frickin’ World Series!” he yelled. His face was so nakedly open and alive. We clutched each other and jumped like little boys.

As champagne sprayed and music blared, Cheo and I ducked under the plastic sheet covering my locker and called home. We could barely hear Mai over the clubhouse noise, and Mai said she could barely hear us over the cheering at their house. Half the neighborhood was there, she said.

“Where’s Pai?” I asked.

“He’s out on the street yelling with the rest of the crazies!”

Soon, though, he came to the phone talking in his happy, Coors Light voice.

“Wow, the World Series!” he kept saying. “Wow! That’s amazing!”

Mai took the phone away.

“Go celebrate!” she told us. “We’ll talk to you tomorrow.”

In the morning, I drove from one gas station to another looking for a newspaper. Every store was sold out. I finally found one in Anaheim Hills.

I looked for my name and Cheo’s in the box score.

There they were. In black and white. It was real.

The team had the day off, so Cheo and I went to breakfast at Denny’s. Fans kept congratulating us and taking pictures and asking for autographs. In the car afterward, we talked about how as kids we had fantasized about playing in the World Series. But we never dreamed we’d be together.

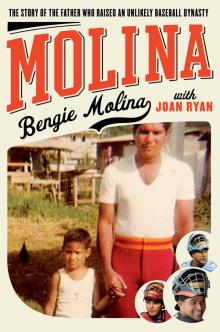

The press took hold of the unusual story. One story was headlined “City of Brotherly Glove.” It recalled how Pai took us to the field every day after work and described Pai’s unorthodox batting grip. “My dad was short,” I was quoted as saying, “but he could hit.”

The reporter wrote: “Bengie, the proud son, talks about his father like a kid whose dad can beat up yours.”

I laughed, because that was exactly how I felt.

Mai and Pai couldn’t come to the Series. Pai was being inducted into the Puerto Rican Amateur Baseball Hall of Fame on the same day as Game 7, if the Series went that long. My wife and daughters couldn’t come for Game 1, either, so I asked Jamie to fly down and use one of the tickets.

I saw her before the game in the hallway outside the clubhouse. She gave me a hug and told me how proud she was of me. That was the only game I could invite her to; my wife, daughters, in-laws, and friends used my tickets for the rest of the games. But Jamie and I talked by phone before and after every game. She settled me. She lifted my spirits when I allowed a passed ball or failed, yet again, to get on base. To her I could admit that I was worn out from the long season. Probably every player was toast by that point. But catchers took a particularly brutal beating. In addition to the usual swelling and bruising, I had developed tendonitis in both knees. I arrived at the park early for my knee-survival routine with the team trainer: ultrasound therapy, ice, hot pad. That was enough to get me through batting practice. Thirty minutes before the game, I took a Voltaren, an anti-inflammatory drug. That got me through most of the game. By the ninth inning, the pain and swelling had returned. I iced again at the ballpark then once more at my apartment or hotel room. Before bed I took another Voltaren to stave off the pain so I could sleep.

I downplayed the pain among my teammates and coaches. I never wanted them to doubt I could answer the bell. Only Jamie knew what I was going through. She was the person I was closest to, who truly knew and accepted everything about me—and she couldn’t be with me at the most important event in my career. I knew she felt hurt and frustrated. She obviously was more than a friend but just as obviously not a girlfriend or a wife. She had no clear or comfortable role in my life. And I had none in hers. It was totally screwed up.

Still I was surprised when, after Game 5, she wouldn’t come to the phone. We lost the game in part

because of a pitch that got past me. Now we were behind three games to two. If we lost the next one, we were done. Jamie always found a way to make me feel okay. I knew she’d tell me to stop obsessing on what I did wrong and focus instead on everything I did that helped the team. I should have been able to tell myself this. But I needed to hear it from her, with that gentle certainty in her voice.

I called a half dozen times. She didn’t answer. I called her roommate.

“Jamie doesn’t want to talk with you right now.”

“Why? What’s going on?”

“That’s between the two of you.”

“Please put her on the phone.”

Jamie wouldn’t come.

The Giants’ Game 6 starter, Russ Ortiz, shut us down inning after frustrating inning. We fell behind 5–0 in the seventh inning, eight outs away from losing it all. When we finally got a couple of hard hits, Giants manager Dusty Baker walked to the mound and took the ball from Ortiz, signaling he was taking him out.

Great, we thought. Ortiz had been giving us fits. We’d much rather face their relievers. Then as Ortiz was about to leave the mound, Dusty Baker did something that ignited a firestorm on our bench. He handed the ball back to Ortiz, like he was giving him the game ball. Like the game was already over.

“Did you see that?” someone in the dugout said.

We had all seen it. If we needed a kick in the butt, Dusty Baker had just delivered it.

In came reliever Felix Rodriguez to face Scott Spiezio. Two men on base. One out. Speeze fought off one pitch after another, fouling, fouling, fouling. Then he laid into one. It sailed toward right field. The right fielder leaped. He hit the wall, impeding his jump. The ball cleared the top of his glove, and the wall, by a fraction of an inch.

Molina

Molina