- Home

- Bengie Molina

Molina Page 18

Molina Read online

Page 18

When he shook his head again the next inning, I called time-out and invited him to join the pitcher and me on the mound.

“Okay, you want to call the game, call it. Fastball touch your head. Curveball to the chest. Slider to the thigh. Shake your hand for the change-up.”

I left the mound before he could answer and squatted behind the plate. The pitcher waited for my signal. I looked at the shortstop. He looked back at me. I waited. The pitcher looked at me, puzzled. I stared at the shortstop.

Bud Black, the pitching coach, called time and walked to the mound. I hustled over to join him and the pitcher.

“B-mo, what’s going on?” he asked.

“We have a situation, Buddy. I think the shortstop is trying to tell us we don’t know what we’re doing. So I’m waiting for him to tell us what pitch we need to call in this situation.”

“Come on, B-Mo, leave it till after the game.”

I returned to the plate, squatted, and looked at the shortstop again. I waited a beat, then finally gave the sign.

Scioscia and Buddy called me into the office after the game.

“You could really hurt the team with that,” Scioscia said. “You can’t let those things bother you.”

He was right. The guy was an idiot, and I let him get under my too-thin skin.

At the end of the season, we faced the Yankees again in the American League Division Series. My bat was so hot that Scioscia kept moving me up in the batting order. I hit sixth in Game 1, fifth in Game 2, and cleanup in Game 3. In the three games, I hit .455 with a home run in each game and five RBIs. When I was hit by a pitch and had to leave Game 3, Cheo took my place and hit a run-scoring single.

One day outside the clubhouse in Anaheim, I heard someone yell, “Hey, Big Money!” It was a janitor who was in the hallway every day. He had a nickname for everyone: Speeze for Spiezio, AK for Adam Kennedy, and so on. He had always called me B-Mo like everyone else did. One of the Angels broadcasters overheard him call me Big Money and used it on the air that night. Soon fans were waving “Big Money” signs in the stands. Other broadcasters picked up on it. The nickname stuck.

We beat the Yankees in five games to move on to the AL Championship Series. In the meantime, Yadier’s Cardinals swept the Padres to reach the National League Championship Series. If we won and the Cardinals won, Cheo and I would play against Yadier in the World Series. It was crazy.

The Wall Street Journal dispatched a reporter to Espinosa to find out what was going on with the Molina family.

“Catchers are an idiosyncratic breed to show up three times in one family,” the reporter wrote. He described Mai and Pai’s house with “paint peeling on the ceilings and the windows held to their frames with masking tape.” Mai and Pai were in the living room watching our games on TV. Mai apparently was yelling at the pitchers for making us dig balls out of the dirt and covering her eyes and praying when one of us came to bat.

José and I lost to the White Sox in the American League Championship Series. Yadier and the Cardinals lost to the Astros in the NLCS.

MY CONTRACT WITH the Angels was up, but I was confident they’d sign me to a new one. I had been with the organization for thirteen years. We had won a World Series together. In the off-season, I waited for my agent to call with their offer.

In the meantime, I found a smallish three-bedroom house with a little yard and a pool in a gated community in Yuma twenty minutes from the house my wife and I had bought. I still hadn’t told Kyshly and Kelssy that I was moving out. They were twelve and nine, beautiful, dark-haired girls who danced and played soccer and knew how to field a grounder on a short hop. They attended Catholic school. Maybe because they had traveled so often to Mexico, Puerto Rico, and California, they seemed at ease no matter where they were or who they were with. They’d meet someone new and soon they were chatting as if they were old friends. I marveled at the ease with which they moved through the world. So different from me.

I told my wife about the new house and when I’d be moving in. Now I had to tell the girls. I practiced in my head what I’d say. When I sat with them in our living room, they were crying before I could get a word out. They already knew from their mother. They begged me to stay. I cried, too, and told them I wasn’t leaving them, only the house. I was their father. I loved them and always would.

They crawled into the crooks of my arms, their faces buried in my chest, their shoulders heaving. My heart was breaking, but I wasn’t changing my mind. This was the right thing. I wanted to give my daughters a happy, loving home. They’d never have that with their mother and me under one roof. I wanted Jamie in their lives. I wanted them to see her strength and independence as a woman, her kindness and compassion. I wanted them to see a healthy relationship where a man and a woman respected and admired each other and were deeply, completely in love. I wanted them to settle for nothing less in their own lives.

When I called to tell Mai and Pai, they already knew, too. My wife had beaten me to the punch.

“How could you do such a thing?” Mai yelled through the phone.

“This has been coming for a long time,” I said, shaken that she was taking my wife’s side in this. “You have to understand that if it didn’t happen now, it would have happened a year from now.”

“How can you do this? I don’t understand!”

“There’s no love anymore, Mai. We’re fighting every day. We don’t even speak. There’s no relationship. I can’t live like that anymore. I don’t want the girls to live like that. Look, I’m not letting go of the girls. I’m going to be there for them. Whatever they need, I’m going to be there.”

I wanted Pai to get on the phone. He’d help me figure out how to get Mai to understand. It hurt that she didn’t trust me to make the right decision for my family. She yelled until she exhausted herself, and finally, thankfully, Pai got on.

“Pai—”

“Your girls are going to suffer!” he barked, livid. “You are the backbone of those girls. You are in charge. You don’t just leave! How can you do this to them?”

I almost couldn’t speak. Did he believe I didn’t think this through? That I didn’t struggle with the decision?

“Pai, you don’t understand. This has been going on for so long. You think everything’s so nice. But all we do is fight. The girls aren’t happy. We can’t go on this way.”

“There is nothing more important than family. You need to go back to her. Go back to the girls. Do whatever it takes.”

My whole life, Pai’s words had been like notes from God. If he said it, it must be true. For the first time, I knew he was wrong.

“You need to trust me, Pai. I’m going to take care of them. It’s the best thing for the girls and for me. They’ll be happier. I’ll be happier.”

He was still steaming when he hung up the phone. I felt sick.

When I called the next day, Mai answered. She had calmed down but was still angry. After a few minutes, I asked to say hello to Pai.

“He won’t come to the phone.”

“What do you mean?”

“He doesn’t want to talk to you.”

I felt as if a truck had hit me. Pai not talk to me? When I needed him most? It was unthinkable. He had been there for me my whole life. He had believed in me. Made me push through the failures. Maybe I should have told him earlier about all this and explained what I had with Jamie, how the love and happiness I felt with her had made me feel whole. But I had been afraid to hear what he’d say. Good people don’t divorce. Good men don’t leave their families. Okay, but at least hear me out. At least consider my side. Was it some kind of cruel test?

“Let him cool off,” Mai said. “He’ll talk to you later.”

But every time I called for the next few weeks, Mai made up some excuse why Pai couldn’t come to the phone. He was eating. He was in the shower.

One day she said, “He’s right here. Hang on.”

Finally.

I heard Pai’s voice in the background

.

“Sorry, mi hijo,” Mai said, “he’s going to the park.”

“Oh, okay. Tell him ‘Bendición.’ ”

My whole life I had sought his blessing. I’d do anything for it. This time I couldn’t. He thought I was tossing away his rules for my flawed ones. He couldn’t see that I was, in fact, living by the values he taught me—family, love, responsibility. I was simply looking at them through my own lens instead of his.

In other words, I wasn’t defying his values. I was, for the first time in my adult life, defying him.

I set up the girls’ bedrooms first so they could start staying with me right away. They stayed at my house regularly, and we’d play Monopoly, Pictionary, Scrabble. We played FIFA video games. Swam in the pool. I would drive them to school and pick them up as often as I could. When they weren’t staying with me, I talked to them on the phone.

I talked to Jamie every day, too, during the off-season. She visited often from Los Angeles, helping me furnish and decorate. But it was too soon for her to meet my daughters.

“THE ANGELS ARE going with Jeff Mathis,” my agent said, referring to the Angels’ top minor-league catcher. It was the autumn of 2005.

I was out. Just like that. Another family broken. I was leaving the only franchise I’d known—all the clubbies, the cooks, the front office folks, the trainers, the coaches, Scioscia, my teammates. My own brother.

My agent said the Mets were offering $18 million over three years. “But I think we can get a few more million,” he said.

“Yeah, you can try for a little more money, but make sure they know I want to make a deal,” I said. “Tell them I’m excited to come to New York.”

I had family back east—my mother’s side in Brooklyn, my dad’s not far away in Connecticut. It was a good fit. I told Jamie and Mai and my brothers that I was signing with the Mets. Now I could relax. I’d have good money for three years.

My agent didn’t call for two days. It was weird. Why was it taking so long to get the deal done? I kept calling my agent and asking what was going on. No one at the agency called back. Four or five days passed. Then I got a message from a friend.

“Did you hear the Mets traded for Paul Lo Duca?”

My stomach dropped. Lo Duca was a catcher with the Florida Marlins. They offer me three years then go and get Lo Duca? What was going on? I called the agency again and finally got a call back.

“What happened to the New York deal? I told you to accept it!”

“Oh, you didn’t want to go there. New York is bad for you.”

“I’m the one who decides where I want to go, not you!”

“I know, but I wanted to use the winter meetings to negotiate more money.”

“I didn’t tell you to wait for the winter meetings!”

I took a breath. I knew people would think I had rejected $18 million. They’d think I was greedy or an idiot. Probably both. I later learned rumors circulated that I was asking for $50 million. I wanted to punch a wall. Or my agent’s face.

“So now what?” I snapped.

He told me not to worry. He was talking to other teams. But I heard a different tone in his voice. He wasn’t as confident as he had been in October.

Suddenly I felt that familiar panic of running out of time—to get on a college team, to attract the attention of a pro scout, to climb out of the minors, to get to the big leagues. Spring training would be starting in two months, and I didn’t have a team.

A month passed. Nothing. Most rosters were set. I just had the best season of my career, and I couldn’t get a job? Scioscia called to see why I hadn’t signed. I found out the Angels had offered a two-year contract—which my agent never passed on to me. He thought he’d be slick and get more years and more money. Jamie called to let me vent. My brothers called, confounded and worried. Mai called, furious.

“Estos cabrones! Son unos stupidos! Que no aprecian!” These assholes! They’re stupid! They don’t appreciate you!

Suddenly Pai was on the phone.

“You have to stay calm in a situation like this,” he said, sounding like his old self. “The game will find you.”

“But, Pai, I was the best catcher on the market.”

“Listen, you can’t control it. There is nothing you can do. So why do you worry?”

His voice calmed me as it always did. He was still there for me.

A week before spring training, Toronto offered one year at $5 million with an option year at $7.5 million. I knew the option was meaningless. It was a guarantee of nothing.

But of course I told my agent to accept the offer. Immediately. Then I fired him.

I flew to the Blue Jays’ Florida training facility. I flew Jamie in, too. I could, for the first time, introduce her as my girlfriend. We were a couple from the start with my new team. There was no awkwardness or explanations, as there would have been with the Angels. After all those years, Jamie and I were together.

On Opening Day, I hit a grand slam to the fifth deck in left field. A few days later, I hit two more home runs. A week into the season, I was hitting over .400 with three homers. Maybe this would be the year I’d hit twenty homers, as Pai told me I could.

But when Toronto’s starting catcher from the previous season came off the disabled list, the manager had us platooning—he started against right-handed pitchers, I started against lefties. It was insane. I was hitting the cover off the ball, and the manager was sitting me because we faced a right-handed pitcher? He had me batting cleanup against lefties, and I was completely out of the lineup against righties?

I was in the manager’s office every other day. How could I keep any rhythm at the plate if I was playing only three days a week? How could I get to know our pitchers if I didn’t catch them regularly?

One day when I called home I was particularly frustrated. Pai answered. We hadn’t talked since the start of the season several weeks earlier and then only briefly. Mai always answered. I started to tell him what was going on. He stopped me and said he’d get Mai.

“Wait—what?”

But he was already gone.

Mai got on.

“Is Pai all right?” I asked.

“He’s fine.”

“He doesn’t sound fine.”

“He’s fine.”

But he didn’t talk to me, not that day or for the rest of the season. I knew by this time that my ex was trashing Jamie and me every chance she got. Crazy, awful stories about us filtered back to me from Puerto Rico. As angry as I was about the lies circulating about Jamie and me, I was more hurt and shaken that Pai could think they were true.

THE SUN IN Yuma in July can bake your eyes right out of your head. But I couldn’t wait to get there during the All-Star Break. The girls were spending three days with me. And so was Jamie. They would meet for the first time.

Jamie and I got the house ready with board games and Styrofoam noodles for the pool. The girls liked her right away. They were open and sweet. Jamie combed their hair after their showers. She and Kyshly played Kelssy and me in Pictionary. We swam and barbecued. We had a beautiful three days.

The girls couldn’t visit me in Toronto because it was too far for them to travel by themselves. Mai and Pai never visited, either. Jamie, as always, got me through. She was still working in Los Angeles but not full-time. So she joined me as much as she could. When she was with me, even just watching TV or eating takeout, I was happy.

If Pai could have felt what I was feeling, he’d have known there was no other choice.

IT WAS WEIRD playing in Anaheim in a Blue Jays uniform. You never knew as a player whether the kinship you felt for the fans was truly reciprocal or if their affection ended when you changed teams. But when I walked into left field to stretch before the game, they stood and cheered.

“Bengie! We miss you!”

“Big Money! When you coming back?”

I stopped at the fence and signed autographs and thanked them for being so good to my brother and me.

It gave me goose bumps. I was still one of their own, even in a Toronto jersey. One of the regular ushers shouted down to me. Every time we had seen each other when I played with the Angels, we would salute each other. As I began to wave, he saluted. I saluted back. Another usher flashed me his usual greeting—the Hawaiian hang-loose sign. I flashed it back, as I had done for years. During batting practice, I hugged my old teammates, caught up with Scioscia, and made plans with Cheo to have dinner after the game. I couldn’t help looking across the field at the Angels’ bullpen, where I had caught warm-up sessions with the starting pitchers. Now coach Steve Soliz was working on footwork with Jeff Mathis, my replacement. I felt a tug of—what? longing? sadness?—the way I did every off-season when I returned to Dorado and was reminded yet again that it was no longer my home.

When I stepped to the plate for my first at-bat, the fans rose in a standing ovation. I was stunned. The cheers felt like a physical thing, a river flowing into me. I stepped out to raise my hand in thanks but also to gather myself. The cheers weren’t for winning a game or hitting a home run. They were for me. Me. The long-shot kid from Kuilan. Who would have ever thought?

In the sixth inning, Cheo reached first base. The next batter up, he broke for second. My brother was stealing on me! I scooped the pitch out of the dirt and fired to second. Too late. Cheo had stolen just 6 bases in 278 Major League games. And he gets one against me.

The next inning, I singled. The third-base coach flashed me the steal sign. What? I had stolen exactly 2 bases in my 721 Major League games. I prayed the pitcher would be slow to the plate. He was. I took off. Cheo caught the ball and leaped to his feet. But no one was covering second! Why would they? Who would possibly expect me to steal? I slid in. No throw. Safe. The whole stadium of Angels fans hooted and hollered. I smiled at Cheo but couldn’t tell beneath the mask if he was smiling back. I was guessing no.

After the game, Cheo and I gave each other crap. I said he got lucky. He said I’d have been out if anyone had been at the bag.

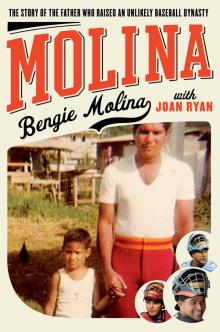

Molina

Molina