- Home

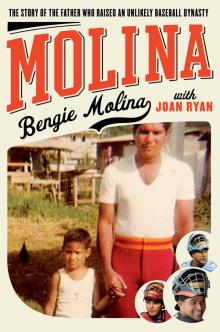

- Bengie Molina

Molina Page 2

Molina Read online

Page 2

“It’s not as if my parents gave him up,” Tío Chiquito told me when I sat with him one day after Pai died. “It’s just that Mama kept him.”

Mama took in other grandchildren as well, about eight in all over the years for various reasons. The tiny house was noisy, a bustling village with Mama as the busy, benevolent mayor. Mama dispatched the grandkids on assorted chores throughout the day, hustling them out with a happy “Get to work!” Some fetched water from the cistern at the side of the house or, when there had been no rain, from the nearby spring or neighborhood well. Some picked pigeon peas and dug up sweet potatoes. Others fed the cow and chickens and collected eggs. Some shucked corn from the field and set the kernels in the sun to dry.

“Ay, bendito, aren’t you ever going to finish?” Mama would tease one child or another.

Mama was never without a kerchief on her head and an apron over her bata. In the kitchen, she ground the dried corn into flour on a hand mill, which she fried up into surullitos, or mixed with milk for a cornmeal mush called funche. When the children played gallitos in the yard, swinging strings weighted with algaroba seeds at each other, they could hear the clatter of her sewing machine rise and fall like a train passing through town.

Benjamín helped Mama with the chores like a little man, like he was her protector. He shot dark looks at his cousins when they showed the slightest disrespect. “Benjamín was good from the time he was born,” Tío Chiquito told me. “He was a being that was born with light. With grace. Mama brought him up almost as if he were a relic. He didn’t get out of Mama’s hands. Benjamín never left Mama’s hands.”

Mama didn’t hide the fact that Pai was her favorite. She whacked the other grandchildren with a broomstick or a branch from the guava tree. If neither was at hand, she’d deliver a good knuckle-thump on the boys’ heads. On the rare occasions she disciplined Pai, she tapped him on the arm with two fingers. On Three Kings Day, a Christmas-like celebration every January 6 in Puerto Rico (and other Latin countries), Mama would give the grandchildren homemade rag dolls and inexpensive toy guns or maracas. She gave Pai a new watch. When she caught one of the other grandchildren wearing the watch one day, she hit him. Mama made sure Benjamín had the best shoes and clothes, though by all accounts he never asked for anything. He was kind and shy like Francisco, barely saying a word even among family.

When there was a celebration, Mama cooked up some chicken, and all her children and grandchildren descended on the house. There might be a bottle of local moonshine making the rounds. One of the men inevitably took out a small guitar with double strings called a cuatro. Others had maracas, bongo drums, and a homemade marimbola—a kind of box with flat strips of metal cut from a car chassis and plucked like a bass. There might be a guira made from a coffee can. They’d play traditional jibara music. Everyone would sing and dance.

But not Benjamín. He was reserved and serious. He always seemed older than he was. People would laugh sometimes to see such a dry face on a young child.

The only place he seemed to loosen up was on the baseball field.

MY BROTHER JOSÉ—whom we call Cheo—and I ran home from elementary school every day and waited for Pai. We lived at that time in Vega Alta, in a barrio called Ponderosa, just west of Dorado. Our house balanced on stacks of bricks, with wooden steps to the front door. It had a small sitting room, a kitchen, and two bedrooms—one for Mai and Pai, and one where Cheo and I shared a bed. The bathroom had a copper pipe protruding from the wall and delivered only cold water. The floor in the sitting room had two holes big enough to watch the roosters from next door wander beneath us looking for shade.

Pai’s shoulders filled the doorway when he walked through, arriving home from the factory. He always wore a collared shirt. Mai pressed it every morning. He wouldn’t put it on until right before he left because the house was hot and humid. I’d eat cereal in front of the TV as Pai, fresh from the shower, padded around bare-chested. Mai made him eggs and boiled hot dogs and coffee. Sometimes I’d go into the bathroom and watch him shave. I’d watch him tie his shoes and hear him wish for ones with more protection around the toes.

I didn’t yet know he was going to work. I didn’t think of him as having a life beyond baseball and us. Mai worked, too, but I didn’t think about where she went, either. Before we were old enough for school, they dropped us off every morning at our grandmothers’ homes—Cheo to Mai’s mother, me to Pai’s. Sometimes I pretended to be asleep in the car because I knew Pai would carry me inside, place me on Abuelita’s couch, and kiss me on the forehead. Soon I understood they worked at factories, Pai at Westinghouse and Mai at General Electric.

When Pai got home, Cheo and I already had our gloves in our laps.

“Bendición,” we said.

“Dios te bendiga,” Pai answered. May God bless you.

There were no hugs and kisses. Just the respectful greeting between children and elders.

Pai set his empty Tupperware container on the kitchen counter; Mai would fill it with the night’s leftovers for Pai’s lunch the next day. Pai sank into the big chair and unlaced his shoes. Mai barked at him from the kitchen not to leave them in the middle of the floor like he always did.

“You’re lucky I come home at all!” Pai barked back.

They went back and forth. But Pai was smiling. And I could see that Mai was smiling, too, just a little, like she was trying not to. This was their routine. They almost never touched each other. I rarely saw them kiss. Pai would never show affection in front of other people. Mai would make a show sometimes of trying to kiss him in public just to get him going. He’d shoo her away. But at the end of the night, they always walked together into the bedroom.

Mai handed Pai a plate of pork chops or fried beef, and he turned on our black-and-white TV to the Mexican comedy El Chavo del Ocho. Cheo and I plopped onto the floor next to him. We’d watch El Chavo, but we also watched Pai. We loved seeing his face relaxed. Sometimes he laughed so hard we could see the food in his mouth. He didn’t laugh much the rest of the time. He still had the serious face he had as a child. He wasn’t a talker. He was the sort of man who told you something once. We never had big discussions. He told us to do our homework and respect Mai and take off our muddy clothes on the back patio by the washer and dryer. When he was angry, he’d look straight into our eyes and not move a muscle. We’d stop whatever we were doing.

Mai was a different story. She was outgoing and opinionated. She was the yeller and the hitter. She’d whack us with whatever she could reach—a spoon, a hanger, the back of her hand. We’d run away and she’d chase us—especially Yadier when he came along. He was the happy hellion. Cheo and I were rules followers, me especially as the oldest. Yadier was all about having fun. He’d tease Mai, grabbing her by the waist and whirling her around to dance when she was sputtering mad. Sometimes she’d end up laughing and dancing; she saw a lot of herself in Yadier. But when she had it in her head to wallop us, there was no distracting her. I remember one time Cheo and I wouldn’t stop fighting. Mai came after me with a belt, and I crawled under the bed. “Don’t worry. You have to come out sometime,” she said. When the sun set and the house was quiet, I slithered out, curled up on the bed, still in my baseball uniform, and fell asleep. All of a sudden I was under siege. Mai was whipping my legs.

“I told you I was going to get you! Don’t ever run from me!”

There were times she’d put the belt to my back and I’d have two long marks that made an X. When I went outside without a shirt my friends would laugh. “What’d you do now?” Their mothers were the same, and most of the fathers, too. Even the teachers hit us. In sixth-grade English, Mrs. Cuello would walk around the classroom with her hands behind her back as she delivered the lesson. If you weren’t paying attention, she’d sneak up and karate-chop your neck. I was extremely introverted and hated speaking in class, much less standing up in the front of the room. When I refused one day, Mrs. Cuello yanked me up to the board, her big old nails digging into my ne

ck. Another time she hurled an eraser at me; I ducked and it hit my cousin Mandy, leaving a rectangle of white chalk on his forehead.

So Mai wasn’t unusual in her physical punishments. She was tough. Nothing intimidated her, not even the roaches and rats that infested the houses in our barrio. You’d open a cabinet and a dozen roaches would scatter. We’d find rats almost every morning in the traps Mai set on the kitchen floor or in the patches of glue she placed under the sink and behind the stove. She had no problem picking up the dead ones—or stepping on a live one if she had to. I once saw Mai twist the neck and snap off the head of a live screaming chicken when nobody else had the stomach to do it. She plunged the body in boiling water, plucked the feathers, and gutted it. Pai, on the other hand, got the heebie-jeebies around a dog or cat. When Mai got a small dog after my brothers and I left home, she asked Pai to give him a bath in the plastic tub outside. He took the dog outside and sprayed him with a hose from five feet away. When Mai saw him, she yanked the hose away and turned it on Pai.

“You like that shower now?” she said.

Pai ran away, dripping wet, yelling at her to stop.

“Don’t even think about going in the house like that!”

Mai was hard-core. She had to deal with four boys. All of us and Pai.

After El Chavo, Pai retreated to the bedroom, changed into his sneakers, and emerged with a canvas bag of bats and balls. Titi Graciella told me Pai went crazy with happiness when I was born because he’d have a son he could take to the baseball field with him. Cheo was born less than a year later. As he grew up, Cheo became handsome, with kind eyes and a sturdy athlete’s body. Like Mai, he seemed always to be smiling. I was serious like Pai. But that’s where the resemblance ended. Pai was built like a block of granite, with a flat, squarish face and cropped hair. I was skinny with a long face, a big nose, a gap between my two front teeth, and crazy kinky hair that Luis the barber would yank so hard my neck would snap back. I’d cry until Pai gave me one of his looks. For as long as I can remember, I cringed when I looked at myself in the mirror.

We piled into the old Toyota and drove to the baseball field, which was a few blocks from that house in Ponderosa. Every town in our part of Puerto Rico had and still has two landmarks: a church and a baseball field. My two brothers and I were baptized in the big church on the Vega Alta town square. My baptism and communion were pretty much the extent of my church experience. My parents weren’t even married in a church. Church weddings cost too much.

As a child, on the few occasions I found myself in the Vega Alta church, I didn’t feel that God would live in such a place. The door was thick and heavy, and when it closed behind me, I imagined being sealed inside an enormous crypt, cut off from everything alive.

The ball field was a different story.

There was grass and sun and, from that earliest memory of Pai hitting the home run, I believed baseball fields were places where magical things happened. Pai’s lessons about the game only deepened that belief. He told us that the foul lines don’t really stop at the outfield fence but go on forever, into infinity. And it was possible, Pai said, for a baseball game to last forever if a team managed to keep getting on base or no team scored. So baseball could defy space and time. That sounded more like God than anything I heard in church.

The baseball field always seemed like an extension of our house, even before we moved back to Espinosa and lived right across the street from the park by the tamarind trees. Pai cared for the baseball fields the way Mai cared for our houses. He brought a rake to clear the rocks and smooth the infield divots. He brought enormous, ten-inch-thick sponges and a wheelbarrow of sand to sop up rainwater. Sometimes he brought gasoline and set the puddles on fire.

He’d push a nail into the dirt by home plate and attach a string. He’d tie the other end to the base of the outfield foul pole. He sprinkled chalk one handful at a time along the string to make straight baselines. Then he’d measure the batter’s box and chalk that, too.

Pai had a system for teaching us baseball. He introduced one skill at a time, making sure we mastered it before moving on to the next. First, he taught us how to catch a ball. For days and weeks, we did nothing but play catch. Two hands. Get in front of the ball. He didn’t yell. He talked. He was loose and comfortable. He talked more in one afternoon on the baseball field than in a week at home. He seemed somehow softer on the field. He even moved differently, with more lightness and grace. He was uncomfortable with affection, but on the field he’d sling his arm around us or pat our faces when we did something well or he wanted to lift our spirits.

After Cheo and I could catch the ball almost every time, he taught us how to stand in the batter’s box. Get balanced. Feet apart, knees bent nice and light. Lift your hands. Be ready to hit. See the ball, hit the ball. See it, hit it! See it, hit it! C’mon!

We were ready to swing for the fences, the way we’d seen Pai and the other men do. No, he said. You learn first how to bunt.

He showed us how to hold the bat so the pitch wouldn’t hit our fingers. Here’s how you drop the bat to the meet the ball.

Finally we got to swing.

Eyes on the ball. Let the ball come to you. Wait for it. See it. Then hit it hard somewhere. As hard as you can. Keep your hands on the bat. Keep your body straight, straight, straight. Okay, you’re turning away from the ball. A lot of players make that mistake.

Sometimes he pitched beans, corn kernels, or bottle caps. He could make them dip and cut, and you had to watch closely to hit them.

He taught us to run the bases—when to round first base, when to run right through it, how to slide. I was light and fast, one of the fastest in my school. I loved running the bases. An irony, I know, given my reputation later as the slowest man in the Major Leagues.

Then he taught us pitching. Rest your glove on your chest. Pick a spot on your catcher. Leg high. Push off. Throw it hard. Down the middle of the plate. Right into the glove. Throw strikes. Keep it simple.

He taught us fielding last. Despite his groundskeeping, the field was still rutted and rocky enough that he was afraid we’d get hurt by a bad bounce. Watch it all the way into the glove. Play the ball—don’t let the ball play you. Bend! Put your glove on the dirt. Stay low. Set your feet.

He told us not to feel defeated when we missed the ball or made a bad throw. Be humble. This is a hard game. The players who succeed are the ones who learn from their failures and then toss them aside. Don’t dwell. Move on. Focus on the next play.

He said whatever good plays we made or good hits we got didn’t matter unless they helped the team win. Every time you put on a uniform it’s to learn and to win. Our own performance was meaningless, because baseball wasn’t an individual sport. Your teammates are your brothers. How can you help them win? How can you help them be better? Pai had no use for players who called attention to themselves or worried about their own stats and accolades.

Be prepared and ready to play, he told us again and again. If you’re not prepared, you’re cheating the game and hurting your teammates. If you lose doing all the right things, you can hold your head high.

When Pai was at work, Cheo and I played on our own. In our street games, the strike zone was a cardboard square taped to a signpost or a chalked square on the side of the house. We wrapped electrical tape around crumpled paper for balls and used broomsticks for bats. We played entire games either by ourselves or with the neighborhood boys—two-on-two, three-on-three. Every boy we knew played baseball. We didn’t get many games on television then. Mostly the playoffs and the World Series. My favorite player was Pete Rose, because he played the way Pai taught us: all out. I never risked my Pete Rose in the baseball card games we played in the schoolyard. There was a number on the back of the cards on the top right-hand corner. We challenged each other, one card against another; the highest-numbered card won. Pete Rose stayed safely in my metal lunch box.

In the street with our broomsticks, I was Pete Rose. I crouched at the plate like

he did. But more times than not, I missed the ball or dribbled it back to whoever was pitching. I couldn’t wait to play on a real team with real pitchers and real uniforms. That’s when I’d show what I could do.

When I was six and old enough for Little League, I couldn’t find a team that had room for me. Some of Pai’s coworkers said their sons hadn’t found teams, either.

Pai found out there was room in the league in Kuilan. So he started his own team there, in the park where he had played as a boy. Pai signed up all of his coworkers’ kids and all the other boys who had been left out. We would stay together as a team for ten years, until we were almost finished with high school. Pai was always our coach.

He called the team Los Pobres.

The Poor.

Pai had a lot of rules. Be on time. That was a big one. No shorts or sneakers. Dress for practice in baseball pants and spikes. Team jerseys were for games only, and they had to be clean. Don’t miss school. Get good grades. Work hard. Support your teammates. Play selflessly. Don’t argue with the umpire. Don’t blame anyone else.

All of Pai’s rules were about the same thing: respect—for coaches, umpires, teammates, teachers, parents, the game, yourself.

During practices, he took time with each one of us. He’d stand with us in the batter’s box, demonstrating how to shift weight from the back foot to the front, how to extend our arms to swing through the ball.

“Great, great!” Pai would say as he threw more pitches. “Again!”

Sometimes Pai would surprise us in practice by throwing a tennis ball instead of a baseball. He’d throw it at our heads so we learned how to get out of the way of an inside pitch. Later he had us swing at a tire skewered on a pole. You had to hit it hard to get it to spin, which trained us to swing with everything we had.

He taught us about strategy. Stealing. Sacrifices. Hitting behind a runner. Mixing up pitches.

He taught us the things that aren’t in the rulebooks, too. Failure is part of the game. You’re going to strike out, get caught stealing, overthrow the bag. Learn from it and move on. If you don’t, the game will crush you. You can’t change what you’ve already done. All you can control is what you do next. What you do now.

Molina

Molina