- Home

- Bengie Molina

Molina Page 4

Molina Read online

Page 4

When I went with Pai, my cousin Ivis and my Titi Pillita, who was just four years older than me, would pull me into some game. But I listened to the adults, smiling at how everybody teased and joked and got each other laughing. When my aunts asked about Mai, Pai would make a big show of rolling his eyes as if to say, “Don’t get me started!” His sisters would laugh and slap him on the shoulder. They loved Mai.

When we left, I’d see Pai slip a few dollars into a purse or onto a counter when they weren’t looking. Then he’d beat a path back to the car. I’d leap up and run after him, turning to wave at my aunts and grandmother.

I knew we didn’t have much money. We had no books in the house except one set of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Pai drove a used Toyota Corolla he bought with five thousand dollars he won in the lotto. We hardly ever went to a doctor. If we had a stomachache or headache, Abuelita would rub us with a special oil. She’d stop a bloody nose with a penny carefully placed on our foreheads. I went to the dentist only once during my childhood. (I finally got my cavities filled and the gap in my teeth fixed when I reached the Major Leagues.)

Whenever Pai heard José, Yadier, or me wishing for brand-name spikes or Lee jeans with the button fly or the nice Toyota with a radio that a high school classmate drove, he’d say, “What they have is what they have. What you have is what you have.” It was a version of what he said on the baseball field. “This is the team we have. This is the situation we have. So that’s what we work with.”

Now after my tantrum over the heavy bat, I thought about what a spoiled, disrespectful brat I had been. I was embarrassed. Mai and Pai did everything for us. I was also scared as Pai opened the car door. I braced for his hit. I knew I had earned it. But he just dropped the canvas bag of bats and balls on the floor, closed the door, and got into the driver’s seat.

I closed my eyes and exhaled, only to hear the back door fly open again. Mai’s hand swooped down on my head, swatting me one last time.

The following weekend, when I walked out of my bedroom in my Los Pobres uniform, Pai shook his head.

“No game for you today.”

Mai, Cheo, and Yadier—who was four years old and already built like a tank—went with Pai to the field. I could hear the shouts and cheers through the jalousie windows. When my teammates dashed into the house between innings to use the bathroom, they asked if I was sick.

“If you don’t want to be in here like me,” I said, “don’t disrespect nobody.”

WHEN PAI WAS a boy, he and his friends hacked branches off trees in the jungle that ran along the edge of Espinosa. They chose the ones with the hardest woods. They whittled and sanded huge bats, carving out a divot at the top and a knob at the bottom like the real bats they had seen.

Pai had been the smallest of all the boys. The first time he tried to swing the heavy homemade bat, it flopped to the ground. He choked up on the handle. Still not enough. He kept choking up until his hands were halfway up the bat, just below the barrel. Finally he could swing with speed and control, if not power. He looked ridiculous. But he could drive anything thrown his way: beans, bottle caps, grapefruit, taped-up baseballs. The unusual grip drove pitchers crazy. He crowded the plate, a necessity when you have only half a bat to cover the strike zone. If a pitcher threw inside, he risked hitting Benjamín and sending him to first. If he threw over the plate, Benjamín could get the fat part of the bat on the ball and slap it through the infield. So pitchers found themselves throwing outside and falling behind in the count, which forced them to lay one over the plate. Benjamín waited for it and pounced.

“Benjamín was the best,” Tío Chiquito told me. “He was tremendous, something incredible. When we were playing in the mountains he would run through those fields like he was a goat and he would catch any ball, it didn’t matter where it was. He was incredible, incredible.”

Pai’s father, Francisco, played some baseball as a kid. Tío Chiquito said he was a catcher for a neighborhood team called Combate. But Francisco worked long hours, and the boys were mostly on their own to learn the game. Pai, Chiquito, their friend Junior Diaz, and some cousins cleared a patch of land behind Mama’s house that had once been a guava tree farm. They dug up stumps and cleared rocks, spending hours and days with shovels and rakes and brooms until they had a small field. They cut four pieces of wood for the bases. The guava trees and the mountain oaks served as the outfield fences.

Mama saved paper bags from the grocer for their gloves. But they’d end up playing with their bare hands because the gloves soon disintegrated from sweat and abuse.

When they could, the boys watched the amateur Class A team in Maguayo, a barrio in Dorado not far from Espinosa. They scavenged the team’s discards for broken bats and ripped balls. They pounded nails into the split wood. They tore away the balls’ tattered covers and wrapped tape around the yarn and cork centers. They practiced every day on their makeshift field, and soon set off to play in their first tournament.

In the first inning of the first game, they were disqualified for the nails in their bats.

Word spread to other neighborhood teams about the kid with the unusual batting grip and lightning-fast speed in the field. When the Guarisco team, in the sector adjoining Kuilan, recruited him to play, Pai was using three pairs of socks as a glove. The other players were bigger and stronger, and most had real gloves. He told his cousin that when the ball hit his hand, he’d feel it in his heart. He learned to block balls with his body. He glided more than darted, getting to the place he needed to be, yet looking as if he’d barely moved a muscle.

Pai and his cousins earned money selling Maria Julia’s alcapurrias door-to-door. She paid them thirty-five cents for every dollar they collected. The boys also scoured trash bins for copper, which might bring a quarter or two. With the money, they bought five-dollar plastic gloves and six-dollar spikes at Bargain Town in Bayamón.

Soon another sector in Espinosa, Río Nuevo, recruited Pai away from Guarisco. Then Maguayo recruited him from Río Nuevo. He was earning a reputation. People came to see this unconventional player who hit everything thrown and caught everything hit.

ONE DAY A storm rained out our practice. Pai pulled on his jacket, grabbed his keys off the kitchen counter, and headed for the door. I knew he was going to Junior Diaz’s.

“Pai, can I go with you?” I asked. I was twelve.

My mother was at the sink washing dishes. She gave my father a look when he said I could go, and I bolted to the car before he changed his mind.

The bar might have had an official name, but all anybody called it was Junior Diaz’s, after the man who owned it. It was around the corner from our house, near La Número Dos, the main street through Dorado. I had never been inside, though I’d seen my father there plenty. From outside, you could see a small counter where Junior Diaz sold beer, chips, candy, cigarettes, and on special occasions asopao, a rich soup of rice, vegetables, and shrimp. Men sat at tables drinking beer and playing dominoes. Kids wandered in with their quarters to buy soda and chocolate.

Pai and I walked in silence. By then the rain had let up and the low sun threw a shadow across the patio as I followed Pai inside.

“Chino!”

“There he is!”

“Ah, my luck just changed!”

“You bring someone who knows how to play?”

Pai laughed and took a Coors Light from Junior Diaz, who had popped the cap before we were two steps in the door.

On the concrete patio were two dominoes tables and a dozen or so mismatched chairs filled with men from the neighborhood, Pai’s boyhood friends. I recognized most of them. They looked like Pai: leathery faces, dark eyes, thick arms. But unlike my father, they had round bellies. My father was still broad-shouldered and narrow-waisted. I could see the muscles of his back move beneath his shirt when he walked.

Pai walked the beer over to the low wall of the patio, poured a few drops onto the dirt outside, then took a long swallow. One of the men pushed his dominoes into the cente

r of the table and rose, nodding at Pai to take his seat.

“This your oldest?” the man asked as Pai sat.

“Bengie,” Pai said. His face was soft and relaxed.

“Bendición,” I said to Junior Diaz’s father, who was my padrino, my godfather. He was the original owner of the bar.

“Dios te bendiga.”

Junior Diaz brought me a Hawaiian Punch in a can. He clapped me on the back and said he hoped I wasn’t expecting to learn anything about dominoes from my old man.

Pai smiled, swirling the tiles on the table.

I leaned against the wall and sipped my Hawaiian Punch straight from the can. I knew better than to ask for a straw.

My father was now slapping down tiles and downing one Coors Light after another. The men bet on the games, but they played for beers, not money. With each beer, Pai became more talkative, as he did after our games when my teammates’ parents—Pai’s coworkers and friends—gathered at our house. He was laughing a lot and telling stories. I laughed at his stories, even the ones I didn’t understand. I studied his face, the flat cheekbones, the straight teeth, the short dark hair specked with gray. He caught me looking at him.

“Another Hawaiian Punch?” he asked.

I shook my head. I wanted to show him I wouldn’t be a bother.

One of the men asked me if I knew Pai had played Double A baseball when he was only fifteen. I didn’t.

“Nobody could figure out how to pitch to him. They throw it here, and he hits it,” Junior Diaz was saying, talking about Pai. “They throw it over there, and he hits it. They throw there, and he hits it.”

Suddenly everyone was telling a baseball story about Pai. They called him el bufalo—the buffalo—and their voices changed when they talked about him. I knew he was famous, though he almost never talked to me about his baseball career. I’d ask him about the trophies in the living room, and he wouldn’t even look up from the newspaper. “That was a long time ago,” he’d say.

As I listened at Junior Diaz’s, I got to wondering. If Pai was so good, why did he work in a factory instead of in baseball? Why didn’t he play professionally? What had happened?

“Your boy play like you?” someone asked.

I felt my face flush. The men were looking at me, sizing me up. What was Pai going to say? I was still one of the worst hitters on the team. I had no home runs. Hardly any singles.

“He has great hands,” Pai said. “The best on the team.”

He told the men he liked me to play first base because nothing got by me. “I know I can count on Bengie,” he said.

I felt a wave of pure pleasure.

When we returned home, Mai had dinner waiting. I ate my food in silence, replaying my father’s words in my head, feeling the same rush of pleasure each time.

In bed that night, I tried to imagine myself in one of the chairs at the dominoes table, listening to the men tell stories about my heroics on the baseball field. But I couldn’t make the picture work. It was always my father in the chair.

SOON AFTER THAT day at Junior Diaz’s, I had a particularly awful game. I struck out three times. With each missed swing, with each lonely walk back to the dugout, I sank deeper into a funk. Pai never let on that he was disappointed or embarrassed, but I imagined him wondering how a son of his could be so spectacularly weak and ineffectual.

After the game, I went straight to my room and closed the door. Later that afternoon, my cousin Mandy tapped on my window. I cranked open the jalousie window.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

“I feel sick,” I said, which was the truth.

When Mai called me for dinner, I told her I wasn’t hungry.

“You’re eating.”

I trudged to the table and fell into a dark silence, not even pretending to eat. Yadier told a story about an argument he had with some kid at school. Yadier never backed down from anyone. He was a tough kid. He attended an elementary school in Vega Alta, like Cheo and I did, because Titi Charo and Titi Yvonne, Mai’s sisters, were teachers there and reported back if we skipped class or got into trouble. Cheo and I almost never did. But Yadier had his own ideas about school. He was smart but never worried about what anyone thought. Mai whacked him and yelled at him, but everyone knew she had a soft spot for her youngest son. She liked his warrior spirit. I listened to Yadier’s stories and wished I were more like him.

Pai suddenly told me to get up. He said to follow him. My mother, brothers, and I looked up from our plates, wondering what had gotten into him. We never left the table during dinner.

“Come on,” he said.

He opened the front door and headed across the street to the field. I jogged after him. Was he going to have me take more batting practice? But he didn’t take his equipment bag.

I caught up to Pai at the gate to the field. He went through and stopped near the on-deck circle.

“Look at me,” he said. His face was soft.

Then he said the very last thing I expected.

“I love you, mi hijo.”

My heart pounded. He had never told me. I was surprised and thrilled and frozen. I wanted to say I loved him, too, but nothing came out.

“Good or bad, I love you,” he said. “You’re going to be fine. God has a plan for you. Do you understand?”

He swept his hand toward the field. “Look at this.”

I looked. The bases. The pitcher’s mound. The backstop. The dugouts.

“See that?” Pai said. “You know it. You’ll be fine. Don’t worry.”

I didn’t know what I was supposed to say.

“Do you understand?”

I nodded. But I didn’t understand.

“Okay,” he said. Then he walked back through the gate and toward the house.

He turned. “You coming?”

I ran across the street and followed him through the door. My mother and brothers looked up from their plates and studied us silently as we sat back down.

What was he was trying to tell me? That I’d be fine in baseball? That I could always come back there?

The next day at school, I told my cousin Mandy what had happened.

“He said that?” Mandy said, wide-eyed, as if I had told him God Himself had descended from the clouds and personally blessed me. “Man, if he said you’ll be okay, then that’s it. You’ll be okay.”

I smiled and nodded.

Pai saw something in me I didn’t yet see in myself. I knew then that I’d start hitting. Maybe not that day. But it would happen.

I knew I had to get stronger. My dad’s cousin had a son named José Miguel, who had recently signed with the Cubs as a top prospect. He was muscular and strong, and once when I saw him at our field, he told me about lifting weights and doing push-ups and other things that could get my body stronger.

On the way home from high school one day I found just what I needed: a metal pole about four feet long, probably from a chain-link fence. I already had two large tin soda-cracker cans, about the size of Quaker Oats containers. We had half a bag of cement in the marquesina, the carport. At that time we were renting a house back in Vega Alta across from the field. I mixed the cement with water on the floor of the marquesina then folded in some rocks. I scooped the mixture into one of the soda-cracker cans. I pushed the pole into the cement and positioned it straight up in the center.

The next day, when the cement was dry, I filled the second can. But this time it wasn’t so easy positioning the pole. The heavy can at the top kept pulling the pole off center. I held it in place until it seemed set. The next day the pole was leaning slightly, but it was good enough. Now I had a barbell to add to the rest of my carport gym. I had an exercise bike borrowed from my cousin Ramirito, Titi Gorda’s son. I had an old tire tied to a rope. I had an ax from my uncle next door. And right outside the marquesina was a tree for pull-ups. I’d do regular push-ups and backward push-ups on the cement floor.

I lifted the barbell every day, sometimes before school, sometimes after.

One of the soda-cracker cans was heavier than the other, so I had to flip the bar to keep from overworking one arm.

I looped the rope around my waist and ran with the tire behind me through the sand at the ball field. I got the idea from Rocky. I ran up our street, which went uphill for about a quarter of a mile and ended at the garbage dump. I ran up and back as many times as I could. Sometimes Tío Felo or one of my cousins would drive me to Breñas Beach or Dorado Beach so I could jog through the sand. I took the ax in the woods behind our house and chopped trees until I couldn’t lift my arms. Another idea from Rocky.

Over the next year, my body filled out. My shoulders broadened. My arms hardened. My swing got faster and more powerful. My eye was sharpening. I was becoming a steady contact hitter. Pai could count on me to execute a hit-and-run or a sacrifice bunt. I moved up in the lineup from eighth to seventh to fifth. Pai even had me leading off sometimes. And he no longer protested when I picked up the heaviest bat.

One day, at our home field in Kuilan, I got a big fat fastball over the plate. I exploded into it, and the ball rocketed into center field. I rounded first, watching to see if I had a double or a triple. The ball kept going. The center fielder backed up to the fence—and the ball sailed over his glove and out of the park. My first home run. I was fifteen years old.

Pai was coaching third, and he had the biggest smile on his face. As I ran past him, I tried to be cool. He held up his hand for a high five. I slapped it and smiled so wide I almost started to laugh.

That was the year I moved up to American Legion ball—Post 48 in Bayamón—while still playing for Los Pobres. I was playing four games a week and improving quickly. I was a key player, by now one of the best. So was José. Unlike me, he was always a star. Scouts were looking at him even though he still had two more years of high school. So many players from Puerto Rico were signing pro contracts and flying off to the States—Sandy Alomar Jr., Benito Santiago, Carlos Baerga, Pudge, José Hernandez, Ruben Sierra, Edgar Martinez, Roberto Hernandez, Rafy Chavez, Luis DeLeon, Miguel Alicea, Pedro Munoz, Coco Cordero, Julio Valera. They’d return for the winter with better spikes, better gloves, new baseballs, new bats.

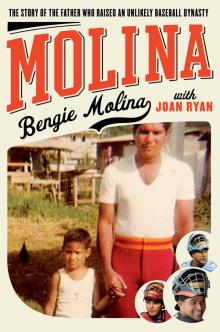

Molina

Molina